Introduction

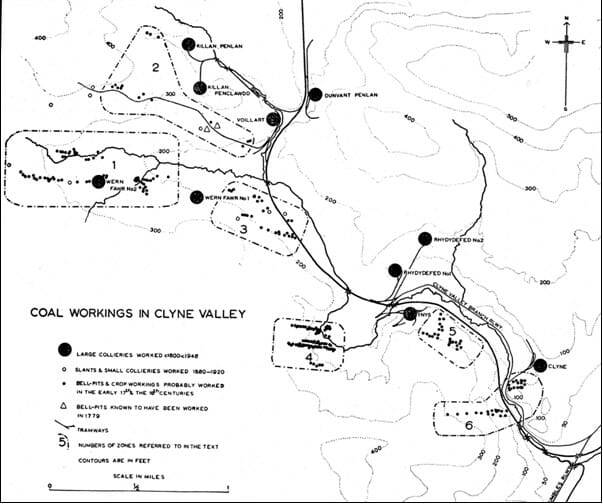

A survey published in the journal Gower in the 1950s identified a total of 255 bell pits within the Clyne Valley between Ynys and Dunvant. They fall into six main groups, two of which (groups 5 and 6 on the map reproduced below) fall within Clyne Wood where the Dukes of Beaufort owned the mineral rights. Sites in zone 5 appear to be earlier on the grounds that they are more degraded and eroded than those in zone 6. They represent clear evidence for early coal working in the Clyne Valley, although it is almost impossible to date them accurately.

Description

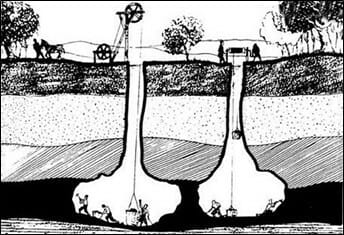

Bell pits (or ‘shaft-mounds’) can be recognised as a fairly shallow depression in the ground, perhaps about 5 to 15 feet across with a mound of earth at one side. They are often found running in a line along the coal seam. They represent an early method of mining coal, which was suitable only when the coal was very close to the surface. A small pit was sunk through the superficial boulder clay. When the coal was reached, the pit was widened or ‘belled’ out as far as safety allowed, 10 feet being the absolute maximum as the loose shales crumbled easily when exposed. Once the coal was removed, the pit was abandoned and a new one sunk nearby, resulting in a line of pits all along the line of the seam as can be seen in a number of places in the Clyne Valley. In some instances, where the coal lay very close to the surface it was extracted by a trench rather than by separate pits. Bell pits have a spoil heap, usually on the northern side which allows the pit to ‘breathe light and air’ from the prevailing south westerly winds to dry out the area.

In Amy Dillwyn’s novel of 1880, The Rebecca Rioter which is set in the 1840s, the villain dies in a bell pit in the Clyne Valley.

Early records

One of the earliest surviving records of coal mining in Swansea relates to the Clyne valley. In an inquest of 1319 the Lord of Gower, William de Breos, was accused of having alienated, among other property belonging to the lordship, mineria carbonum maris juxta la Clun cum molendino aquatico de la Blakepulle [‘mines of sea coal near the Clun together with Blackpill water mill’]. In fact what de Breos had probably done was to grant the recipient of the property in question, John de Horton, the right to work the coal and to take the profits in return for a royalty.

There is clear, if discontinuous, evidence of coal mining in Clyne Wood in the 17th and 18th centuries. It was probably these coalmasters who were responsible for the bell pits. In 1642 Richard Seys was granted the right of ‘digginge of coales in Clyn fforest’. Richard Seys was a leading figure in Swansea at this period and as well as the Clyne coal he was also working coal in the manor of Millwood (now the Brynmelin and Manselton districts of Swansea). There is further evidence for coal working in Clyne in the 17th century in the form of a deed of 1662 relating to royalty payments due to the Duke of Beaufort and in 1689 John Watkins of Gellihir (in Gower) was granted a lease of coal under Clyne Forest. Watkins was an active coalmaster: he also worked coal at Waunarlwydd and at Loughor. By 1697 Isaac Hamon could write of the ‘ … forest of Clyne, where is great coale workes besides the veines of Coales there unwrought’.

Two isolated statements of land money, i.e. royalties, due to the Duke from the proprietors of Clyne Colliery survive for 1751-2 and 1753-4. In 1751-2 export sales to sea were 85 weys and landsales were 20 weys. In 1753-4 the equivalent figures are 287 weys and 76 weys. A wey was a measure of volume not weight, but it is generally reckoned that at this period it was the equivalent of five tons. This produces an annual output in 1751-2 of 525 tons and in 1753-4 of 1,815 tons. The colliery was perhaps worked by the partnership of Champion and Griffiths who were recorded as the lessees of the coal ten years later in Gabriel Powell’s ‘Survey of the Lordship of Gower’ of 1764. Powell noted that ‘these mines at present yield but very little profit’ and that Champion and Griffiths had surrendered their lease’. Champion could well be William Champion (1709-1789) the distinguished metallurgist and copper master of Bristol. Griffiths may have been James Griffiths (d.1763) who is also known to have been working coal at Fforestfach and in north Gower at this time.

Much of the coal was probably shipped through Blackpill, for a chart of Swansea Bay dated 1794 shows an ‘Old Quay’ on the beach opposite Blackpill. Possibly this quay, or a predecessor, can be dated to the late 16th century.

damaged through the activity of mountain-bikers (NGR SS 90745 92022)

Gower vol. 11 (1958), p. 19)